The Speicherstadt was the most modern logistics centre of its time. The “City of Warehouses” with its sophisticated handling and storage technology and workers specialising in unloading and processing goods put Hamburg at the forefront of world trade and made the city a centre for luxury goods such as coffee, tea, wine, tobacco and carpets.

Trade and movement of goods in the Speicherstadt

Today, the port of Hamburg is a goods transhipment centre of immense global importance. The port owes this importance mainly to two events without which such a development would not have been possible: the granting of duty-free status by Emperor Barbarossa in 1189 and, of course, the opening of the free port after the customs union 700 years later. As early as the beginning of the 9th century, the Saxon fortification of Hammaburg, as a river crossing and border trading post, played a role in securing the north and east against hostile peoples. Under the reign of the Counts of Schauenburg, Hamburg rose to become a trading centre when Adolf III of Schauenburg granted the new town, founded in 1188, city rights directly with the customs privilege it had just received and had a harbour built on the Alster. The attractiveness of the trading place, which was linked to the exemption from customs duty and the location, ensured an expansion of trade and economy and thus of the entire city.

Bild.

When Hamburg joined the Hanseatic League in 1358, the city had already established trading relations with London, Scandinavia and the Atlantic coast of southern Europe that were indispensable for East-West trade. The port of Hamburg had become a hub for a wide variety of negotiable goods from all kinds of regions. The staple right, introduced some 100 years later, which obliged all merchants passing through Hamburg to offer and sell their goods in the city, also contributed greatly to the flourishing trade. But as long-distance trade and maritime shipping became more established, Hamburgers became aware of the limited capacity of its port.

By the end of the 18th century, Hamburg had extended its trade routes to America and the West Indies, East India and China, as well as the north east of Europe. The port was bursting at the seams. By creating new berths in the form of mooring posts and clusters of piles, the capacity of Niederhafen was increased several times. In 1862, a modern port was finally built at Sandtorkai, which finally put Hamburg in a position to cope with the never-ending and ever-increasing movement of goods. In 1881, the now Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg gave up its customs privileges under pressure from the German Empire and integrated itself into the German customs territory, but only under the condition of its own free trade zone – the Speicherstadt.

In 1888, the free port, including the warehouses and offices, was opened in a ceremony by Kaiser Wilhelm II. At that time, the most modern goods handling and logistics centre in the world was now located on the city’s doorstep.

The significance of the Speicherstadt for Hamburg’s trade and movement of goods

At first glance, the construction of the Speicherstadt did not seem to have any notable benefits but only disadvantages. The construction of the free port and the associated customs union buildings meant an immense personnel and financial effort for the city to maintain or recover a status quo that Hamburg had enjoyed for centuries previously. However, in retrospect, the Speicherstadt was exactly what Hamburg had been lacking to advance to the top of world trade. Hamburg’s merchants did not benefit from the free port per se, as they were quite familiar with this special role, but they were able to capitalise on the modern buildings with their state-of-the-art winches and cranes, as well as the location directly on the waterfront and the associated short distances between the ships and the concentrated warehouse blocks, which were divided up according to types of goods. The newly established coffee exchange, for example, leveraged these advantages to make Hamburg the market leader in coffee trading.

The benefits of the warehouses and offices

The dockside sheds and the warehouses served different purposes in their functions, thus the professions required for the work to be performed there also differed. The dockside sheds were intended to ensure rapid transhipment between the ships and the port, while the warehouses were used for the long-term storage and processing of goods.

In these sheds, the goods brought to the shed by ship or train were sorted and stored until they were transported to the warehouses. During the unloading of the cargo, the goods were delivered to the dockside shed, while the reverse would see the goods being removed from the shed to be loaded onto a ship or railway wagons. In order for the sheds to meet their requirements, the dockside sheds were built with a large open space without many restricting beams or walls. This meant that the goods could be easily accessed and clearly stacked. In addition, even, bright daylight was provided to ensure tasks such as weighing, label reading and sorting could always be carried out as accurately as possible. An extra room was set up for administrative and clerical work.

In the warehouse buildings, the ground floor of the buildings, which had an average of six storeys, was normally used as an office; the remaining storeys served as storage space. The top floor also housed the internal lifting equipment, such as hydraulic winches, with which the goods were hoisted from the barges or carts to the individual storeys, the ‘floors’. The individual floors had a load capacity of 1,800 kg per square metre. In addition, the warehouses were designed so that the same ambient conditions could and did prevail there every day of the year. The ambient conditions could be adapted according to the goods stored. Thus, the stored goods could permanently be protected making it possible to store spices, nuts, coffee, tea, tobacco and rugs.

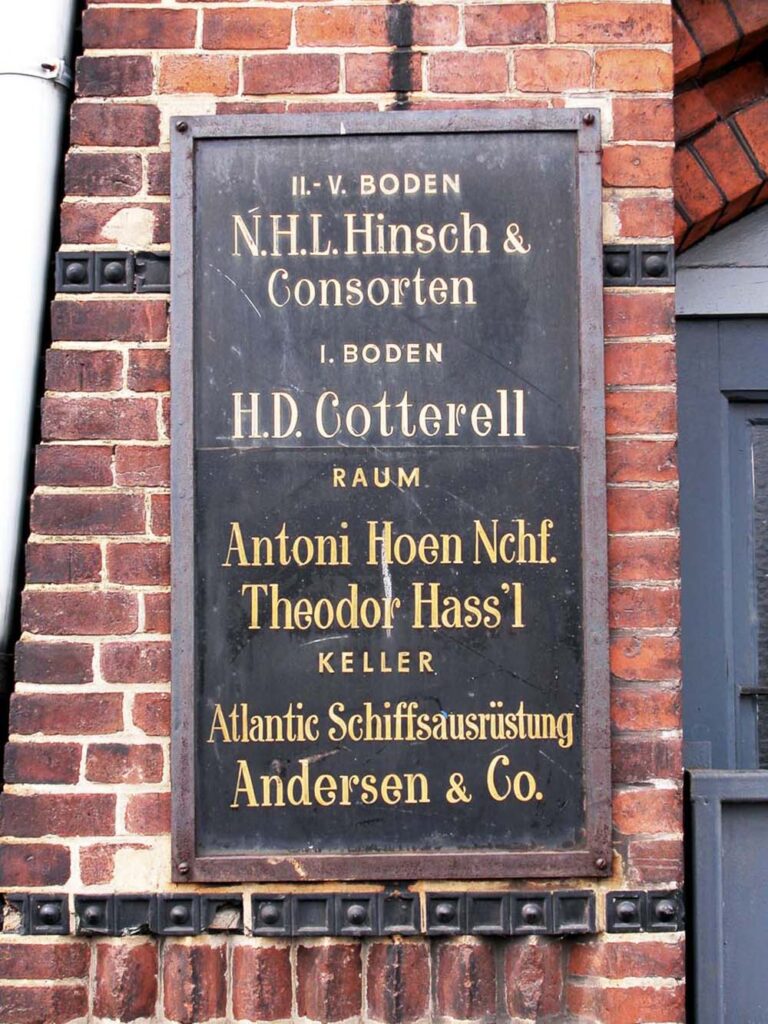

Quartermasters

Most of the storage facilities and storage blocks were not used by HFLG/HHLA, but were let, the majority of them to quartermasters. The quartermasters, as the warehouse keepers in the Port of Hamburg refer to themselves to this day, were commissioned to store and process the imported goods. They do not act ‘on their own account’, but trade on behalf of various merchants. They look after the goods from delivery to collection, carry out professional quality controls and take care of all processing and storage. They are also responsible for the smooth processing of all formalities from customs clearance to forwarding to the customer. The profession of the quartermasters has been documented in Hamburg since 1693. The name derives either from the quarter in the literal sense, where the quartermasters stored their utensils, or from the Latin term ‘Quarta’, as four quartermasters always gathered. The name of one of these men plus an appended ‘& Consorten’ gave the company its name, but most of them were known by their ‘Ökelnamen’ (nicknames), which were derived from their character, origin or faith, and when they were mentioned, everyone in this profession knew immediately who they were talking about.

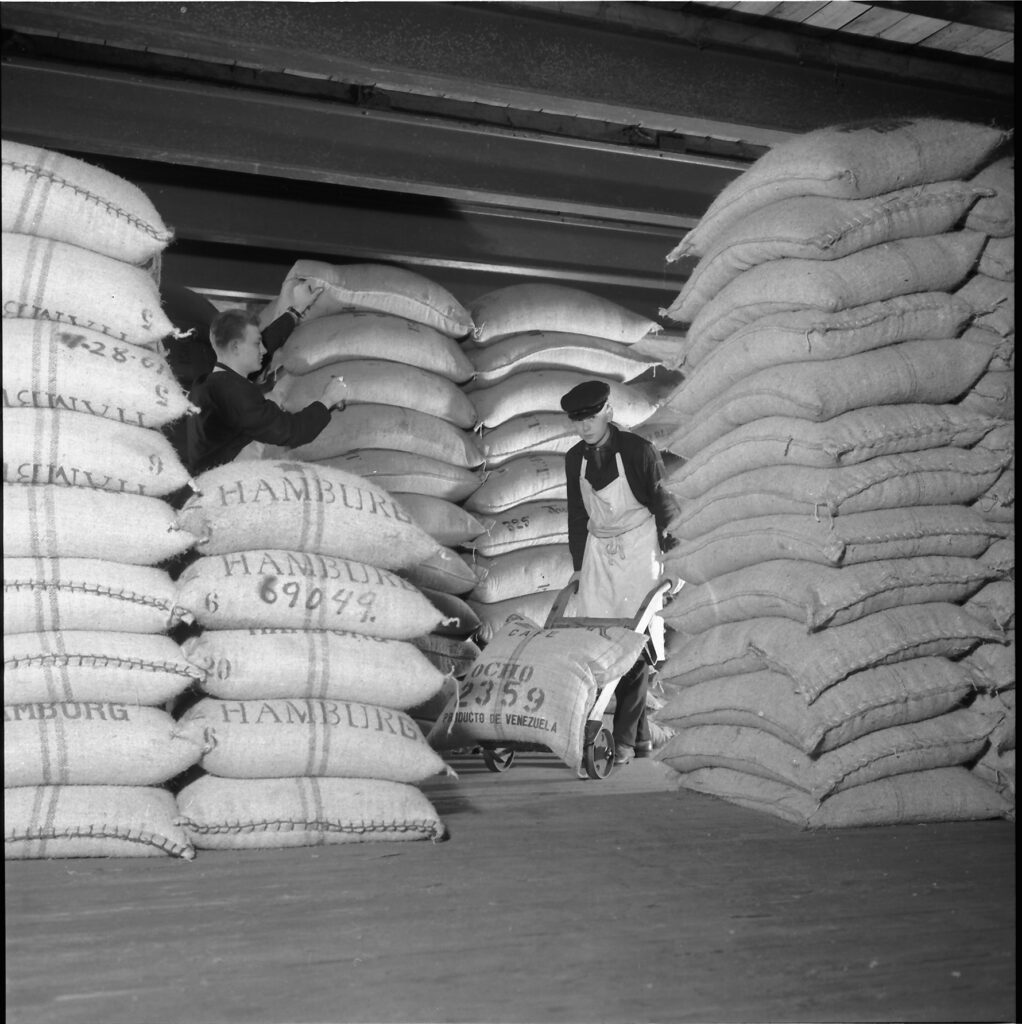

Originally, they were hired by the merchants to carry out the work that had to be done and commissioned in their warehouses, which also included the delivery of the new goods. For the merchants, the quartermasters’ assessment of the goods was the basis for their price calculation. The construction of the Speicherstadt gave them the opportunity to open their own warehouses in addition to their actual activities. This was more than welcomed by the merchants, as they thus found, from the very beginning, trusted and above all competent contacts who could guarantee the proper inspection, storage and processing of the goods. Individual companies acquired their own fleet of vehicles so that they could deliver the goods sorted, cleaned and mixed in their company directly to the merchants’ customers. At times there were more than 80 groups of quartermasters with over 300 members. Quartermasters typically wore a black jacket with silver buttons, an apron and a top hat, which only came out on festive occasions. When working on the floors, they wore a linen cap with a short peak as head protection.

Coffee trade

The coffee trade was of paramount importance for Hamburg. Hamburg merchants and shipowners had established direct access to the coffee plants through several branches at export locations, making Hamburg one of the most important transhipment centres for coffee in the world. For this reason, when discussing the possibility of a customs union, most coffee traders were strictly in favour of maintaining the free port status. And their word carried weight, as they were by far the largest and most important lobby. This is even stated in the 1887 annual report of the Hamburger Freihafen-Lagerhaus-Gesellschaft (HFLG) with the words ‘that coffee is the main item stored’. The coffee trade, including the coffee storage facilities on the eastern Sandtorkai, was concentrated in blocks O and N. At the centre of the coffee trade, was the ‘Coffee exchange’. 14% of global coffee trade was conducted at this location.

Only members of the coffee association were allowed to trade there duty-free. However, only those who were engaged in international coffee trade and had at least two advocates could become members. The futures business with coffee was quite lucrative. Example: 5000 bags of beans of Santos coffee. Bought in March, with delivery planned for May. If the price rises by then, there are big profits to be had.

The stock exchange was filled with agents who selling all kinds of samples and offers from various producing countries. The importers used this option of mediation through agents, they never bought directly from a producer or exporter. The agents in turn remained loyal to the importers and did not trade directly with their customers. The coffee was sold according to the product samples available or according to a description if samples were not available. Ultimately, the delivered goods had to match the samples or description for the trade transaction to be completed. According to Hanseatic tradition, the spoken word formed the basis for the conclusion of a contract. Trading on the stock exchange was unrefined. If you hesitated too long and were left empty-handed, heated conversations were held, which could end in insults and a mutual ‘office ban’. With the start of the ‘Great War’, the coffee exchange was closed and only reopened eleven years later. This was the time when the coffee market experienced a renewed boom.

Wine, tea and tobacco trade

In contrast to coffee, tea was a much smaller item, both in terms of quantity and trade volume. One reason for this was the yield of the tea. A pound of coffee might last a few days, whereas a pound of tea would last a whole month. The trade in tea was considered the most elite branch of business in the Speicherstadt. Small goods for a small, distinguished circle. Fittingly, the British Empire was regarded as the main trading partner. The tea merchants were located at Neuer Wandrahm and Pickhuben.

The tobacconists were also located at Pickhuben. They traded tobacco varieties from overseas and in large quantities from the Near East, mostly from Turkey. After the First World War, the ‘Orient’ cigarette, which had enjoyed great popularity in the trenches on the front, replaced the cigar among consumers. The trade in wine was also significant and equivalent to the trade in tea or tobacco in terms of volume. The special thing about the wine trade was its storage. Wine merchants needed special storage buildings, as the wine had to be stored separately from other goods in premises of a different design. The wine merchants had to apply for, commission and fund the buildings themselves.

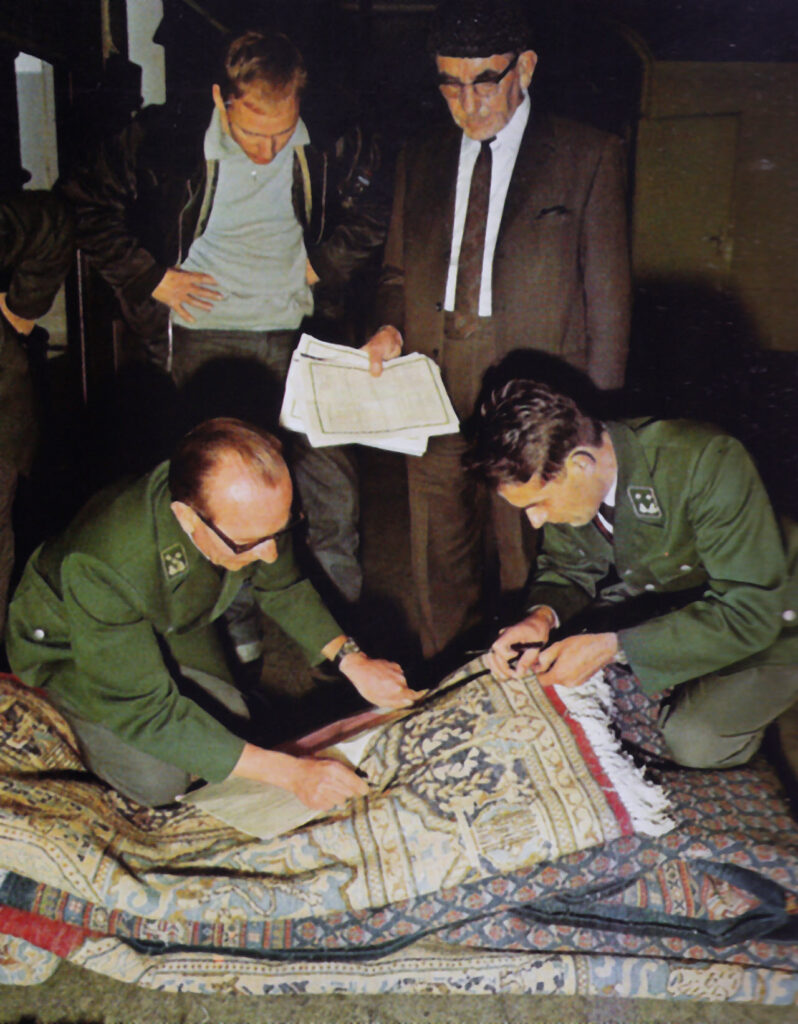

Rug trade

While not considered during the construction of the Speicherstadt, oriental rugs are still traded in many places in the Speicherstadt today and fulfil all the conditions for being stored there. An oriental rug often has to be stored for a long time before a buyer can be found. The ambient conditions in the old warehouses with their coolness and darkness at constant humidity are perfectly suited for this. The Speicherstadt is the largest oriental rug warehouse in the world. At Speicherstadt’s height, up to 60% of storage space there was let to rug traders. The first Oriental rugs found their way into the living rooms of wealthy Hamburgers as early as the end of the 19th century courtesy of Turkish-Sephardic Jews.

However, the rug did not undergo the transition to a profitable stock item until the mid-1950s, when the Wirtschaftswunder (German economic miracle) made Persian weaving affordable for the broad masses, the middle classes.

This business was boosted and made socially acceptable by Iranian students who initially sold carpets from their homeland to finance their medical studies and later sold them instead. It was not long before the oriental rug had established itself as a status symbol in the households of Hamburg. By the 1970s Hamburg had become the world capital of the rug trade. In the late 1980s/early 1990s, almost 350 companies vied for customer attention in the Speicherstadt. After Iran and India, Germany imports its oriental carpets most frequently from Nepal, China, Pakistan, Turkey, Morocco and Afghanistan.