The Kontorhausviertel is located closely to the Speicherstadt. The densely developed area is characterised by large office complexes that were built to accommodate companies with port-related activities. Together, these neighboring quarters form an excellent example of a combined warehouse and office district connected to a port city. The part of the Kontorhaus quarter known today as Meßberghof was originally named “Ballinhaus” in memory of the director of HAPAG who gave the name to the building, Albert Ballin.

History of the Kontorhaus District

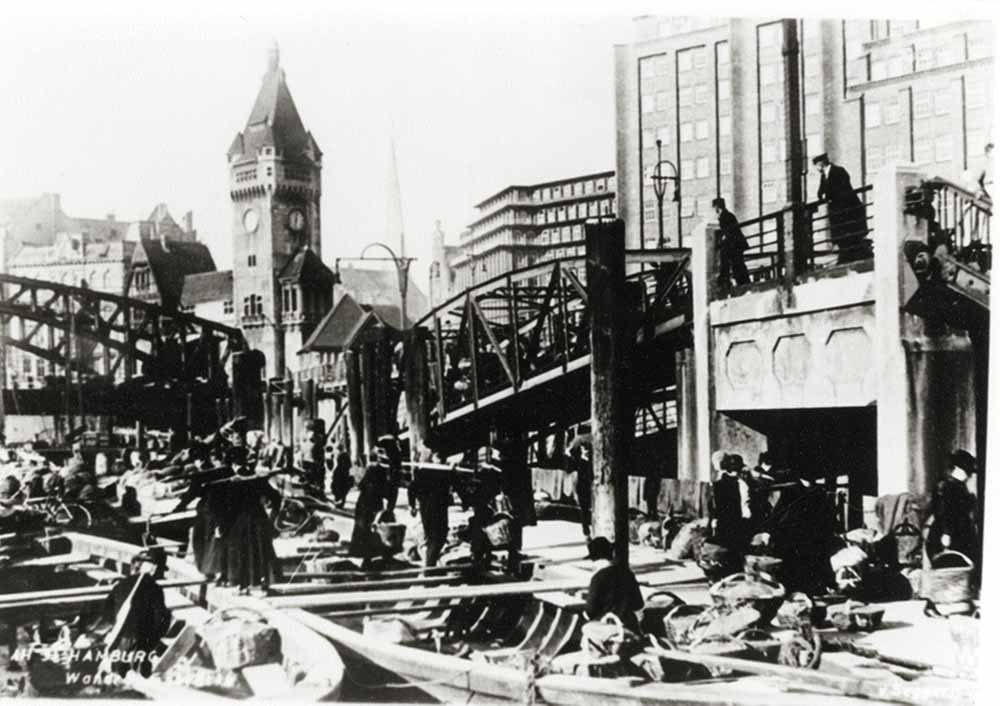

After the devastating cholera epidemic in 1892, the Senate decided to redevelop large areas of Hamburg’s old and new town. First, the new town was redeveloped. Since the redevelopment area in the old town was very extensive, the measures here were divided into chronologically consecutive sections. Initially, the area north of Steinstraße was redeveloped from 1908 to 1913, including the approximately 750 m long Mönckebergstraße, which was reserved exclusively for office and retail space. Subsequently, the restoration of the historic residential area from the pre-industrial era, which is in the south-east of the Hamburg-Altstadt district between Steinstraße and Meßberg, was tackled. In this area, on the north side of the Customs Canal, in the immediate vicinity of the Speicherstadt, the Kontorhaus district was built in the 1920s and 1930s, and as well as parts in the 1950s. The district’s name refers to its mono-functional use as tenement office buildings, which have been commonly referred to as Kontore [offices] in Hamburg since 1910. The district was once connected to Speicherstadt by the bridge Große Wandrahmbrücke, which has since been destroyed. Today, Wandrahmsteg, which is slightly offset to the original, provides this link. The Chilehaus, Meßberghof, Sprinkenhof and Mohlenhof that form the district’s core zone stand out from the remaining buildings in the Kontorhaus district because of their exceptional architectural quality. With the exception of the third construction phase of the Sprinkenhof, all these buildings were built during the Weimar Republic and are among the most important office housing designs of their era.

Construction of the Kontorhaus District

After the residential area (Gängeviertel) was demolished, construction efforts moved to upgrading the road network. As with the Speicherstadt, there was a massive clearing of living quarters and residents had to move away from the district. The existing streets were considerably widened and straightened, and new streets were added and extended. The result of this rigorous intervention was oblique-angled plots of land that challenged the creativity of the architects, which was particularly evident in the case of Chilehaus, for which 69 individual buildings had to make way. The streets of the Kontorhaus district were laid with large granite paving and filled with tar, with its kerb stones also made of granite. The street network in the Kontorhaus district has been largely preserved in this condition to this day. At that time, trees along the streets were not a common feature in Hamburg’s city centre. Fountains, monuments and other decorative elements in urban spaces were also dispensed with, except for the square at Meßberg. It was this dry design that gave the Kontorhaus district its special character. As a result, the Kontorhaus buildings were able to dominate the urban space of Hamburg city centre without restriction. What is striking here is the uniform urban character. Most of the buildings constructed up to 1931 are large-scale, block-filling buildings with clinker façades, white mullioned windows, flat roofs and staggered storeys. The buildings from the Nazi era deviate from this scheme, especially with their pitched roofs. The Kontorhaus district can thus be identified as a closed quarter that stands out significantly from the Hamburg city centre, both in terms of its scale and its design. This has meant that one of the most impressive cityscapes of modernity of the inter-war period was created, which is second to none not only in Germany, but also on an international scale. From this unique ensemble, the core zone, consisting of the Chilehaus, Meßberghof, Sprinkenhof and Mohlenhof, again stands out clearly due to the architectural, urbanistic and conceptual quality of these buildings.

The Chilehaus

The Chilehaus was commissioned by Henry Sloman and as one of the first buildings in the Kontorhaus district was built from 1922 to 1924, based on a design by Fritz Höger. It has listed as a protected monument since 1983. With up to ten storeys and 36,000 m² gross floor area, the Chilehaus dominates not only the Kontorhaus district, but the entire neighbourhood not only in terms of height, but also in terms of mass. The street Fischertwiete cuts through the middle clinker-fronted building with its flat end. This street was spanned in such a way that two separate buildings were turned into a single structure with three inner courtyards. The façade sections at Fischertwiete, which mark the centre of the building, are elaborate. Fischertwiete was converted to a pedestrian zone in the 1990s. The clinker façade with vertical, horizontal and often axis-wide projections and recesses is broken up by means of pilaster-like façade pillars and service-like templates protruding from them. The architectural sculptures and also parts of the finishes in the entrance halls were created by Richard

The Chilehaus is a reinforced concrete skeleton construction on a pile foundation partly made of concrete piles and partly of timber piles. The latter are driven into the ground in groups and connected by iron-reinforced concrete caps of 1 m diameter. Iron-reinforced concrete piles are cast on the caps. Expansion joints are installed between the building sections so that partial subsidence of the building in problematic ground does not affect the entire construction.

Meßberghof/Ballinhaus

The office block on at Meßberg originally named and known as Ballinhaus was built between 1922 and 1924 by the brothers Hans and Oskar Gerson. In 1938, the building was renamed by the Nazis to Meßberghof, due to the Jewish origins of its namesake Albert Ballin. It is still referred to as this to this very day. The bust of Ballin standing in the entrance hall was destroyed too. One disconcerting fact is that the company Tesch & Stabenow, which supplied the poison gas Zyklon B to several concentration camps, had an office in the Meßberghof from 1929.

The Meßberghof is a reinforced concrete skeleton construction. In contrast to the Chilehaus, the Meßberghof has flat façades with only minor divisions, which are largely austere. The purist aesthetics of the materials are also generally characteristic of the Gersons’ designs. As the original sandstone sculptures by Ludwig Kunstmann were severely damaged by weathering, they were removed in the 1960s and replaced by sculptures by Lothar Fischer in 1996/97.

The staircase, with its innovative design of a spiral stairwell and reaching through all floors as far as the eye can see, which is topped by a crystal-like skylight, was hardly frequented from the beginning. Instead, equally innovative paternosters moved people between the individual floors. The building was listed as a historical monument in 1983.

Albert Ballin and the HAPAG

Albert Ballin was born in Hamburg on 15 August 1857 as the son of Samuel and Amelia Ballin, Jews who had immigrated from Denmark. He was the youngest of 13 siblings, his father owned the emigration agency Morris & Co, which he had founded in 1852. In 1899, Albert Ballin was appointed General Director of HAPAG, and in 1900 HAPAG was officially regarded as the largest shipping company in the world. The new company strategy devised by Ballin was to make the size and comfort of the ships the main attraction. Ballin’s motto was ‘luxury not speed’; passengers should feel that every day spent on the ship was a gift. As a result, HAPAG entered the competition for the world’s largest and fastest ships in transatlantic traffic. Successfully, of course. In 1900, the Deutschland won the ‘Blue Riband’; in 1905, the Amerika was launched, followed by her sister ship, the Empress Auguste Viktoria, which entered service in 1906 as the largest ship in the world, and finally in 1912, the Imperator, the first ship to bear a male name at the behest of the Kaiser.

Ballin and the Kaiser

Although Kaiser Wilhelm II appreciated proudly armoured cruisers and sleek yachts, he was also fascinated by glamorous luxury liners. That is why, during his visits to the Hanseatic city, he was captivated not only by the maritime character of Hamburg, but also by its shipping companies, and especially by HAPAG and its director, Albert Ballin. This is how it came about that Ballin first resided as a guest at the imperial court in the summer of 1901. Soon afterwards, Kaiser Wilhelm II actually visited Ballin at his residence. After his first visit to Ballin’s house, Wilhelm II repeated this every June until 1914. The monarch retained his friendship with Ballin for a long time, even wanting to make him a minister several times, which Ballin refused to do each time, citing his religion. However, Ballin did not have much influence on the Kaiser, even though he was always said to have had it and was even criticised for it. Wilhelm II valued Ballin’s company as a way to pass time; for especially important matters, he had other advisors to turn to.

Ballin’s death

Albert Ballin died on 9 November 1918, the same day that Kaiser Wilhelm II announced his abdication from the throne and his departure into exile. His life ended at the same time as the German Empire became a republic. When, at midday, State Secretary Scheidemann announced the end of the war from a window of the Reichstag building, doctors in a clinic on Mittelweg in Hamburg were still trying everything to save Ballin; an hour later he was dead. He was 61 years old. His death certificate showed ‘bleeding from stomach ulcer’ as the cause of death. However, friends and colleagues of Ballin assumed that Ballin had committed suicide, some even reported that Ballin had poisoned himself or must have done so on the evening before his death. Whether this was an accident or whether he deliberately committed suicide has never been resolved. However, the poison, ‘sublinat’, which proved lethal for Ballin – difficult to distinguish from a stomach ulcer without an autopsy – was neither freely available for sale nor could it be confused. Statements made by Ballin himself, in which he repeatedly expressed his weariness of life, support the suspicion of suicide. It is therefore quite likely that Albert Ballin deliberately took his own life. Albert Ballin was buried in Ohlsdorf cemetery on 13 November 1918. Thousands of people were present to accompany him on his last journey. His daughter Irmgard died of the Spanish flu only a month later. She was survived by three small children.

Sprinkenhof

The Sprinkenhof is the largest building among the Kontorhaus buildings. It was built in three sections and, because it is divided into three clearly identifiable construction phases, it does not look like a single building, but rather like a group of buildings. The cube-shaped central building was constructed between 1927 and 1928, the subsequent western part was completed between 1930 and 1932, both according to designs by Fritz Höger and the Gerson brothers. Five years passed until the eastern annex was built, and from 1939 to 1943 it was finally erected by Höger alone. The Sprinkenhof’s architecture turns its back on the verticalism of the Kontorhaus tradition, which the Chilehaus had taken to its peak.

Although it was constructed as a reinforced concrete skeleton structure, it was encased in a flat clinker façade. The originally cube-shaped isolated middle section thus gained a solemn dignity that is a major departure from the Kontorhaus tradition. Here, as with the post-war buildings that surrounded the Kontorhaus district, it becomes clear that the homogeneity created by the block development and the almost exclusive use of brick for the façade design is deceptive and that the buildings in the district have a high degree of individuality and differing aesthetic expressiveness. The staircases also remain a unifying element, which here too express the high representative quality of the structures. The building was listed as a historical monument in 1983.

Mohlenhof

The Mohlenhof office block was designed and built in 1927 and 1928 by the architectural collaboration of Rudolf Klophaus, August Schoch and Erich zu Putlitz. The simplicity of the flat-roofed seven-storey building – with additional staggered storeys – reflects the architectural trends of the late 1920s. The continuous, serially sub-divided perforated façades on the street sides are clad with clinker and the inner courtyard is plastered and painted in a light colour. The main entrance is accentuated by a sculpture and relief by Richard Kuöhl, which are made of real tuff stone. It depicts Mercury carrying a cog on his shoulder and holding a figure of Hammonia – the symbol of Hamburg – in the shape of a small kore sculpture in his hand. This larger-than-life sculpture is flanked on both sides by a relief depicting scenes symbolising the five continents. As with the other Kontorhaus buildings, the entrance hall of the Mohlenhof has a lavish design. The floor is made of white marble, the walls are covered with travertine panels. The building was listed as a historical monument in 2003.

Further buildings:

Miramarhaus

The Miramar-Haus building was constructed between 1921 and 1922 as one of the first large office buildings and was designed by Max Bach. The commissioning client and building owner gave the house its name, Miramar Handelsgesellschaft m.b.H. The building’s layout was adapted to incorporate the surrounding streets running at a slightly acute angle. The rounding of the building towards the street corner was exceptional for the time and became a style feature of many of the subsequent buildings. Damage caused by bombing during the Second World War led to the loss of its original pitched roof. During reconstruction it was replaced with a flat roof. The four upper storeys and the staggered storey have been finished with clinker cladding, while the two plinth floors are plastered. The entrance portal on the longer, left side of the façade is particularly elaborate. A frame decorated with ornaments and sculptures extends over both plinth floors. The entrance on the ground floor is set back, creating an open vestibule. The inscription ‘MIRAMAR’ is written in golden lettering above it. This is followed on the upper plinth floor by a group of three windows that belong to an office room, but are integrated into the entrance area by their frame. The two sets of three figures in the frame’s verticals frame are by Richard Kuöhl. They represent professions typical of Hamburg’s economy. An angel hovers to the left in the frame’s horizontal above the entrance. The building was listed as a historical monument in 1999.

Montanhof

The Montanhof, built between 1924 and 1926 according to the plans of the architects Hermann Distel and August Grubitz, is located on the south-west edge of the Kontorhaus district. It is characterised by an expressionist form concept. The middle of a total of three façade sections is represented by three triangular oriel windows. The pillars, each of which connects three of the very narrow window axes, protrude into the staggered storeys like Gothic flying buttresses. Forms of that ‘Gothic’ era are directly reproduced in every detail, the spirit of which Expressionism dreamed about and the design logic of which seemed to correspond to that of the Hamburg Kontorhaus buildings. The building was listed as a historical monument in 2001.

Burchardstraße 19

Built 1954 – 1955 by the architects Puls & Richter for Dobbertin & Co. It is not, as one might think, a reconstruction of a war-damaged building, but rather the most recent building complex built after the Second World War, and completed the Kontorhaus district. With this construction, the architects continued the modernism of the 1920s. A design that is also expressed in the façade – a structured building with ‘a high-rise’ and staggered storeys. In contrast to the neighbouring older Kontorhaus buildings, the bi-colour façade (grid and infill), the elasticity of the structure and the slimmer proportions give the building a certain lightness that is typical of post-war modernism. This design provides a new accent and completes the Kontorhaus district also in terms of architectural history. Very present in terms of urban design at the northern exit of Kattrepel to Steinstraße, the building represents a characteristic feature of the cityscape. The building was listed as a historical monument in 2000.

Former post office and telephone exchange

The Reichspost’s telephone exchange and post office was built in 1924–26 by post office building officer Martin Thieme. Above its ground floor (originally the post office), which was treated as the plinth, the building is characterised by smooth clinker brickwork with minimal ornamentation and minimal relief, and features impressive ceramic portals and complementing entrance as well as wide triangular windows. The main zone of the façade is symmetrically structured. The central compartment, which is emphasised by closely placed pillars with triangular pilasters, is given a solid frame by smooth single-axis sections; this tripartite structure is continued in the staggered storeys. The staggered upper end forms a particularly charming feature due to the special, profiled protruding ceramic covering of the pilaster strips. Influences of the Chilehaus architecture are noticeable, but thanks to the structure of the façade, the building develops its own character, and despite the more subdued division between the expressionist Montanhof and the functional Mohlenhof, represents a characteristic complex in the Kontorhaus quarter. The building was listed as a historical

Police station

The police station was built in 1906–1908 by the architect Albert Erbe. The building is part of the World Heritage site and was designed in the style of the Hamburg Baroque town houses. It is not an actual Kontorhaus building, but it finishes the south-west corner of the Chilehaus. The building was originally constructed for the administration of Hamburg’s rural areas and is adorned with sculptural decoration depicting fishing and agriculture. The building was listed as a historical monument in 1999.